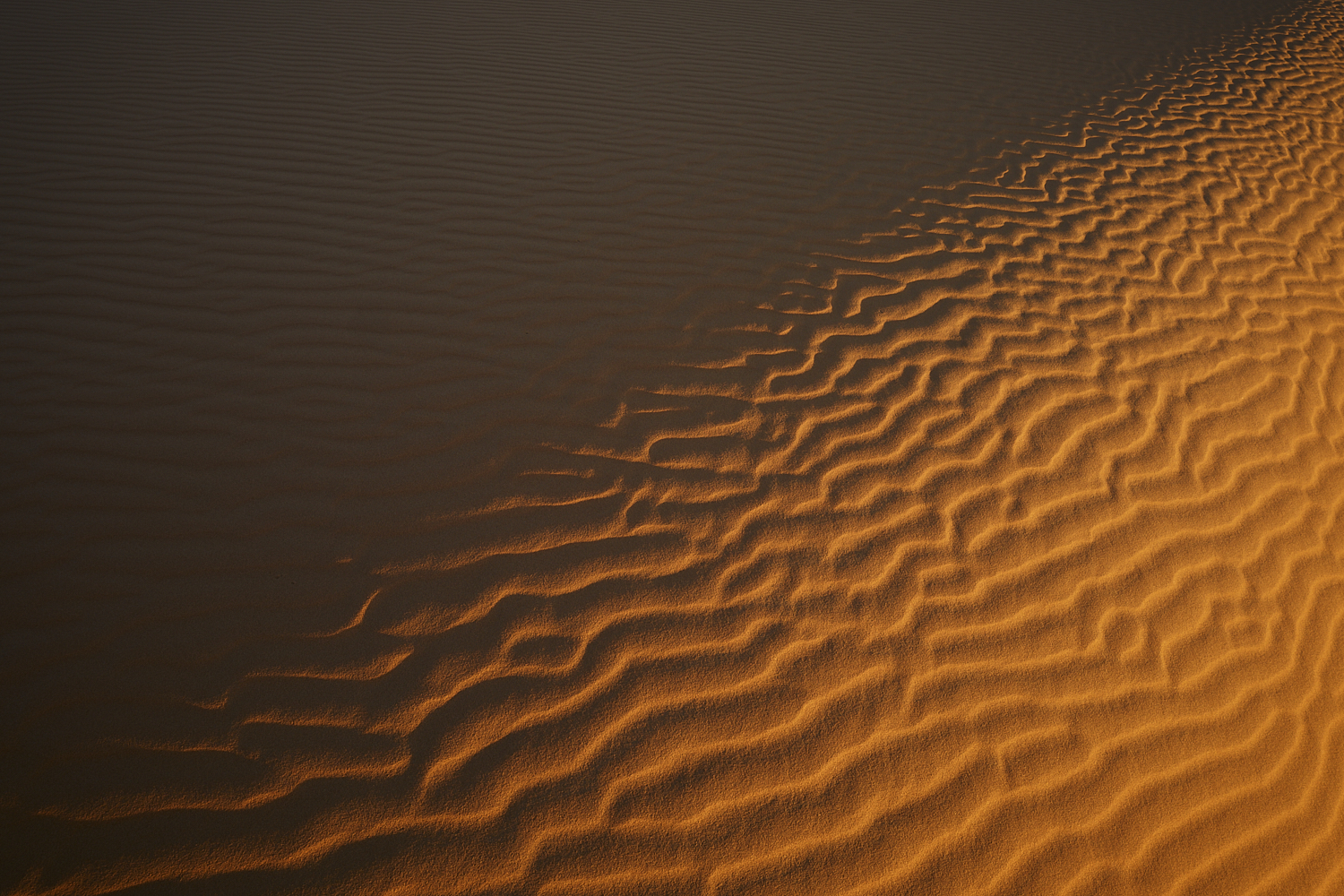

Every step is heavy, and my legs are burning. Even with the goal just within sight, I don’t seem to get any closer. With each step, I sink deep into the sand and immediately slide half a step back down the steep dune. My tripod, which I had rarely used until now, comes in handy as a somewhat heavy walking stick. Just in time for sunset, I reach the “summit” of the dune – completely exhausted and already dehydrated. The hardships of the journey have definitely left their mark on me. I find myself in a physical state I had hoped to avoid here, at what feels like the end of the world and without cell reception. After more than 3,000 km by bike, I have arrived in the Sahara and stand amidst one of the most breathtaking landscapes I have ever seen. Somehow I can hardly believe it myself – maybe I’m just too tired. Alongside the joy of having made it – I had dreamed of this moment for over a year – disappointment soon sets in. To reach a dune landscape as untouched as possible, I had traveled to a remote area. Yet everywhere, tire tracks from 4×4 vehicles crisscross the sand. Exhausted, I unpack my camera and still try to find a few shots without too many 4×4 tracks.

From the last small shop, I had to carry enough food and water for two days over 60 km. But somehow the water supplies are running dangerously low, and most of the more than 4 liters of drink have already been consumed. I would love to trade one – or even two – packs of cookies for some water. But instead, I have to crawl into my sleeping bag thirsty, and of course, what had to happen, happens: In the middle of the night, I wake up with a cramp in my leg. The cramp is extremely stubborn. With a face twisted in pain, I try to stretch the affected muscles, which unfortunately doesn’t work very well. So I crawl out of the tent very carefully, almost cramping my abdominal muscles as well. Once outside, the first task is to stand up carefully and take a deep breath. A few steps on the now-cool sand seem to work wonders, and the cramp disappears. I still have a whole pack of electrolyte tablets with me, but with too little water, they are of little use in this situation… I allow myself a small sip of water anyway, hoping it’s enough to prevent the cramp from coming back.

I sleep surprisingly well until the alarm rings. Still in the dark, I set out toward the largest dune, hoping for new views and photographic perspectives.

On the way back to civilization, I intend to take a drink every 10–15 km, keep my mouth closed, and breathe as much as possible through my nose. Relieved, I first notice only the faint outlines of the settlement. Just 10 km to the next water bottle! But already in the outskirts of the town, I spot a small stand by the roadside offering freshly squeezed lime juice. I immediately stop and treat myself to a glass – it’s wonderfully refreshing! On my very first excursion into the desert, I had already felt the harsh, life-hostile conditions on my own skin. After this experience, I find it all the more fascinating how some plant and animal species can survive under such circumstances.

Since I came up with a few new photo ideas on the way back, I decide to return to the area – this time with 7 liters of water.

The closer you get to the equator, the shorter the golden hour becomes. To my dismay as a photographer, here in the Sahara in Morocco it currently lasts barely 30 minutes. On the bright side, the light changes extremely quickly at sunrise and sunset.

The silence of the desert night is magical. It is almost eerily quiet – so quiet that I can hear the gerbils running across the desert sand. At the beginning of the night it is pleasantly warm, but it cools down quickly, so that in the morning it is chilly and I go out on a photography hunt in thermal underwear and a down jacket.

With the gravel bike, over 30 kg of luggage, and the relatively narrow 42 mm tires – rather slim for sandy terrain – making progress on the tracks is a real challenge. On sections with some sand and stones, full focus and skill are required; in deep sand, it becomes very exhausting pushing the bike. However, since I cover the vast majority of my tour on the road, I accept this as a trade-off between moving efficiently on the road and tackling the – relatively short compared to the overall distance – unpaved sections. So far, the ARC8 Eero has done an excellent job: over 3,500 kilometers to the Sahara without a single mechanical failure. Moreover, at least it feels like with every kilometer on the sandy tracks, my skills improve, and I almost get into a flow over the bumpy paths.

Unlike me, there are true desert specialists who would probably laugh at me when they see me slipping around in the sand or pushing my bike, dripping with sweat. One species that can move particularly swiftly over the sand is the greater hoopoe lark. Given its name, I can hardly help but like it – I enjoy running myself and am fascinated by the desert. Unfortunately, it is also exceptionally good at running away from me. It took me a while before I could finally photograph it up close and in decent light.

True to its German name (Wüstenläuferlärche which would translate to desert running lark), the greater hoopoe lark runs – or rather sprints – across the dunes of the Sahara.

Other desert specialists high on my “wish list” are the sandgrouses. Every morning, they search in flocks for a suitable water source. To photograph them, I am, exceptionally, accompanied by a guide this time. The guide has prepared a waterhole, which he can fill with water immediately upon our arrival. As we wait, my tension rises – will the sandgrouses find the water source quickly today as well? First, we hear their calls. The calls grow louder and louder. Eventually, the flock flies over our heads. This spectacle repeats several times; they seem to be inspecting the water source. My index finger starts tingling with anticipation, but I cannot yet press the shutter. The sandgrouses are, so to speak, teasing me with their flybys. At the worst possible moment, a semi-wild donkey discovers the water source and quenches its thirst there. That silly donkey! Luckily, it doesn’t empty the trough entirely, so some water – and my hope of photographing the sandgrouses – remains. Shortly afterward, the sandgrouses land in the area again. They approach the water source on foot.

Again and again the crowned sandgrouses pause and inspect the area.

Finally, they are very close, and my admittedly not-so-great patience is no longer put to the test. In the foreground is the male, followed by the female.

Upon reaching the waterhole, they drink greedily and leave again as quickly as possible. While it felt like hours until they arrived at the waterhole, they are usually gone again within a few seconds, vanishing into the vastness of the Sahara. When drinking and leaving the waterhole, they seem to be about as patient as I am when I feel that a few more appealing shots might soon be possible.

During my hikes in the dunes, I’ve already spotted tracks of one of the Sahara’s most famous animals several times. However, actually finding the fennec (or desert fox) itself at dusk is difficult. Since I had cycled all the way into the Sahara, I didn’t want to fail so close to my goal, so I contacted a photo guide. Judging by the many photos on his Instagram account, I was already dreaming of amazing fennec shots. With the guide, it shouldn’t be too difficult… Indeed, he quickly finds the first fennec.

Thanks to its characteristically large ears, the fennec can not only detect mice from a great distance across the vast desert, but also cool down more effectively. Very practical – those multifunctional ears.

Just as quickly as the guide found the fennec, it unfortunately disappears just as fast, vanishing behind the next dunes. We don’t see a second individual all evening. On the second night, we don’t even spot a single fennec, so these documentary photos remain my best ones. I had hoped for a lot more beforehand, especially after seeing all the amazing images the guide had shared on social media. As a result, the fennec tours have so far become my biggest disappointment during the Velomad project – I had dreamed of better photos. This also shows me how easily I am influenced by images online or on social media, and how quickly my expectations rise. Not everything can work out perfectly on the first try, even if you want it badly and have traveled over 3,000 kilometers by bike to get there.

In stark contrast to the fennec tours, the trip with Valentin, Demian, and Milan turned out to be a highlight. On their journey through Morocco, they had stopped in the Sahara searching for rare mammals. After a month on the road, I was thrilled to see some fellow travelers again. Together, we check empty water tanks in search of animals that have fallen in and now face a brutal death from heat or starvation. Once an animal slips in, getting out without help is almost impossible – unless you have Milan’s parkour skills.

I have to admit, though, that at first I didn’t really dare climb down into the tanks myself and instead helped get my colleagues out again. 😉 Most of the time, we only find the remains or carcasses of animals, occasionally a few gerbils. Suddenly, Milan yells at Demian to jump back immediately. Right behind Demian’s foot, the head of a Sahara horned viper appears. What a find – and after so many dead animals, finally a living one. But how do we get the viper out of the tank? After a brief discussion, we come up with a plan, and a few minutes later the viper is out. To my delight, its horns are very pronounced. Instead of dying miserably in the tank, the Sahara horned viper even lets itself be photographed for a moment. It’s a win-win situation. I’m sure the viper would have agreed to the deal 😉

In the next tank, it’s finally my turn to slide down. However, once again, we only find animal carcasses inside. The heat in the tanks – thanks in no small part to the black lining – is unbearable. I can’t get out without help. Just a few minutes inside are enough to imagine how quickly one – or the animals – would perish there. I’m therefore very relieved when, on my second attempt, I manage to grab the rescue pole and get back out. It remains a mystery to me why these water tanks aren’t better secured to prevent animals from getting in. A simple tarp along the fence could already help and prevent many animals – including quite a few cats – from dying inside.

The encounter with the desert horned viper was one of the highlights of my first days in the Sahara, not least because the meeting – unlike the one with the fennec – came completely unexpectedly. The desert, as a habitat of extremes, left a deep impression on me and captivated me. Apart from the 4×4 tracks in the sand, the dune landscape is even more fascinating in reality than I had imagined. Now it’s time to get back on the bike, hoping to photograph more animals and landscapes in the desert.

Leave a reply